The Global Horizons program permitted me to undertake intensive work with objects, library research, and collaboration with colleagues in Bern and nearby. While I was primarily at the Abegg Stiftung in Riggisberg, Switzerland, I also had the opportunity to work with relevant art collections and meet with scholars in Zürich, Fribourg, Lausanne, and, of course, Bern. Both my research project nearing completion as well as the one just beginning concern the transmission and translation of cultural ideas around several mythical creatures in visual culture, encompassing a wide swathe from medieval Spain to China.

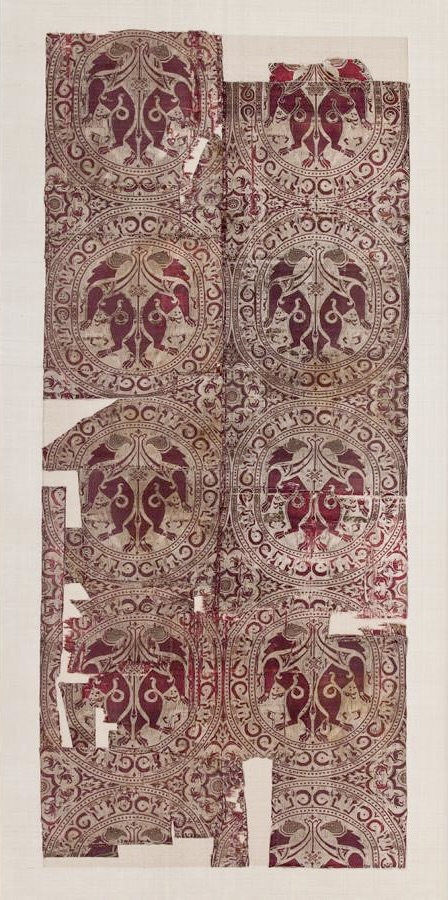

Fig. 1. Griffin-patterned silk from Siguenza, Spain, 1st half of the 12th century, silk (lampas), h. 137 cm, w. 59 cm, Abegg-Stiftung inv. no. 2656/2660, © Abegg-Stiftung, CH-3132 Riggisberg, (photo: Christoph von Viràg)

This griffin-patterned silk offers an interesting example of the textiles explored further in my book to be published by Reaktion Books UK in 2024, Griffinoloy: The Griffin’s Place in History, Myth, and Art. While this piece was found in the Central Spanish shrine of Saint Liberata in Siguenza, where did it originate? Its purpose, enshrouding the saint’s relics, suggests it was made in the first half of the twelfth century, for the relics came to the shrine between 1147-1157. The image of the griffin was remarkably wide-spread, with the earlier examples found over 5,000 years ago in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, and its geographic spread encompassing Europe and western and central Asia. Its persistence and range suggests its appeal to a wide range of constituencies, and is from a group of silks anchored in the al-Andalus textile workshops of Almería, heavily influenced by work from Baghdad, as explored in recent work by Corinne Mühlemann, another scholar I was able to meet while in Switzerland.

Fig. 2. Two fragments of gold fabric with castles, dragons, and griffin pairs, Italy, 2nd quarter of the 14th century, Abegg Stiftung inv. no. 210 a, b, © Abegg-Stiftung, CH-3132 Riggisberg, (photo: Christoph von Viràg)

This piece now at the Abegg Stifting is comprised of two fragments from a gold lampas-weave depicting castles, dragons, and griffin pairs. It was made in Italy, during the second quarter of the fourteenth century, and other fragments from the same textile are now in Chicago and Detroit. The research of Evelin Wetter, an Abegg Stiftung curator who very kindly supported my research there, points to interesting ways its imagery can signal layers of meaning drawing from courtly literary traditions. Thus elements often dismissed as merely “decorative”, such as mythical beasts, inhabit several layers of meaning for their medieval (and modern) viewers.

Fig. 3. Robe with lions and dragonfish, Northern China, Liao Dynasty, 1st half of the 11th century, silk (samite, weft-faced on both sides), padded and lined, h. 148 cm, inv. no. 5239, © Abegg-Stiftung, CH-3132 Riggisberg, (photo: Christoph von Viràg).

The playful reworking of animal forms extends to medieval China as well, and getting to see items such as the Liao dynasty silk robe with lions and dragonfish was a highlight of my work in Switzerland. This outer garment, part of a whole ensemble that is quite astonishingly preserved, features in my next research project. Four lions chase a flaming pearl, a detail often present with dragons. Here instead bands of dragonfish fill the areas in between the lion medallions. The Liao dynasty, from the nomadic Khitan peoples of northeast Asia, favored such imagery, and we find dragons chasing the flaming pearl–often seen as a symbol of enlightenment– on other Liao art and then in turn more widely across Chinese, and ultimately Asian art.

The Abegg Stiftung, distinguished for its vast repertoire of historical textiles, provided an unparalleled environment for this academic investigation of medieval textiles adorned with representations of mythical creatures such as the griffin and dragon. These textiles transcend mere functionality, operating as conduits of cultural expression, symbolic representation, and artistic endeavors. Further enriching the academic experience was the Abegg Stiftung’s robust dedication to research and conservation. Such resources were instrumental in contextualizing the import of griffins and dragons within the broader medieval visual culture and their subsequent impact on art and cultural studies.