During my time as part as a fellow at Global Horizons, I was working on two different projects. The first, a book which centers on the circulation of art and material culture in the Black Sea during the Middle Ages, where I examine how Europe negotiated with its frontier societies in the Black Sea and especially the Crimea, and deployed new technological means in artistic creation to subjugate indigenous population in its frontier territories. The study hopefully will combine, for the first time, an analysis of colonial European art and indigenous art produced by local populations. Amongst other, I hope my study will also shed new light on the origins and foundational aspirations of European Globalism in the 16th-19th centuries. Because of the Covid pandemic, while in Europe, I was not able to travel to the Ukraine and Russia, and so decided to focus on another book-length project.

This project, centers on the sentiment of Hope as a category for artistic creativity. This is a cross-disciplinary project, still in stages of development, involves not just the visual arts but also comparative literature, psychology, anthropology of religions, and sociology.

This project had benefited greatly from my stay in Bern. One rainy morning, together with another Global Horizons fellow, Samuel Luterbacher, I embarked on a research trip to the remote Hermitage and church of Notre-Dame de Longeborgne which is located nearby the small village of Bramois, in the heart of the Valais. The hermitage, first constructed in 1522, when the residents of the village of Barmois handed over some of the caves located in the wild forest mountainous region (Fig. 1) to a group of Franciscan monks whose have maintained the hermitage and erected a church to the Madonna. The church then swiftly became a popular pilgrimage site throughout Switzerland. Apart from two altars, the interior of the hermitage is covered with more than 185 painted panels known as ex votos (Fig. 2). These rectangular wooden painted panels, each displaying some earthly misfortune which, surprisingly, is intersected and saved by divine intervention.

Three centuries of painted ex-votos are visible in Longeborgne. They represent the most important collection of ex-votos in the Valais. An ex-voto such as the ones in the church, are painting, object, or plaque bearing a formula of recognition, which is placed in a church, a chapel in fulfillment of a vow or in gratitude for a grace obtained. The term comes from the Latin “ex voto suscepto” (in accordance to a vow made). These votive panels are the clear expression of an aftermath of an event, where the sentiment of hope, was a catalyst in its making. The painted panels themselves, are the outcome of the sentiment of hope. Their existence is a fulfilment of a vow, who’s in its heart lies hope. Hope that was made into a vow, and was fulfilled and therefore a panel came into existence. The formulaic representation on these panels always narrates an event containing divine intervention. The examples at Longeborgne are striking. An ex voto dated to 1847, shows, in somewhat Caspar David Friedrich manner, a man standing in front of the Hermitage, with the Madonna and Sorrow hovering in the skies above (Fig. 3).

For the man, the ex voto could have either given as a sign of Hope or as a thank you for wish received. The Hermitage and the surrounding nature all mark the centrality of the place in relations to hope. Hope is accomplished or fulfilled when devotee and sacred place intersect. The votive panel is a testimony for human wish and place intersecting. In another, earlier example, a man kneeling, hat thrown on the grounds before him, marking a completion of a pilgrimage, and harnessing relations between sacred space and pilgrim (Fig. 4).

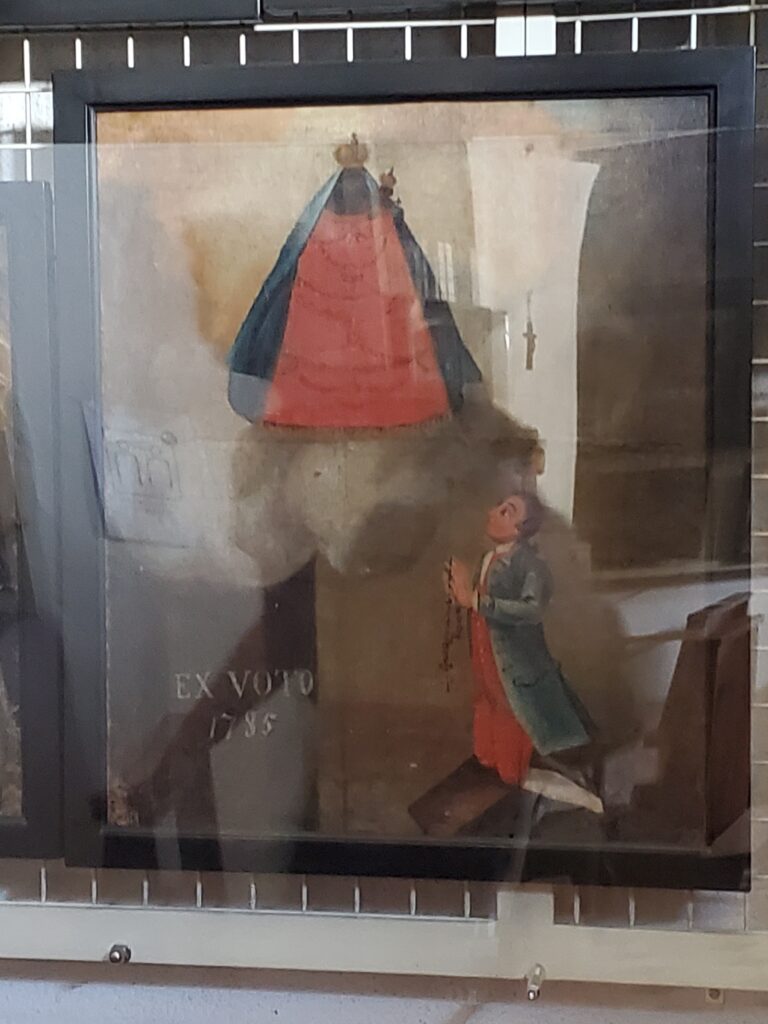

His hands are brought together, marking hope for a wish to be fulfilled. Another panel, dated to 1775, shows a man kneeling in front of the Black Madonna (Fig. 5). The panel seems out of place, for the Hermitage at Longeborgne is dedicated to Our Lady, and the Black Madonna has a shrine dedicated to her in the monastery of Einsiedeln more than 200 kilometer away. We can only assume that the panel was offered at Longeborgne because the devotee, whose name is missing from the panel, could not make the long journey from Valais to Einsiedeln in east Switzerland.

Maybe one of the striking examples at Longeborgne is the panel displaying a carriage accident (Fig. 6), where the hope for the intersection of the Virgin Mary of Longeborgne has saved the humans in their misfortune. The two men standing to the left of the carriage, seem shouting in distress for the Virgin to Help them, they are not begging, but almost demanding divine intervention. Hope is an image for the moment, a visual manifestation of psychologically driven physical desire. It is a visual proclamation grounded in the history of gestures that is embedded in something deep, that connects to the sincerest moments on interiority, when the soul manifests itself physically. At the Hermitage at Longeborgne, the votive panel marks hopeful desires that are unique for the time and the place but at the same time could be found throughout, Switzerland, and beyond.