Leaving Kyoto for Tokyo on Thursday morning, we looked up in the sky and noted its resemblance to an airy batik silk spreading above our heads. Not the clouds were attached to the blue ground—it was almost like the in-between had been dipped into blue dye, absorbing it to various depths. We did not know we would encounter more outstanding blue-grounded textile creations later in the day.

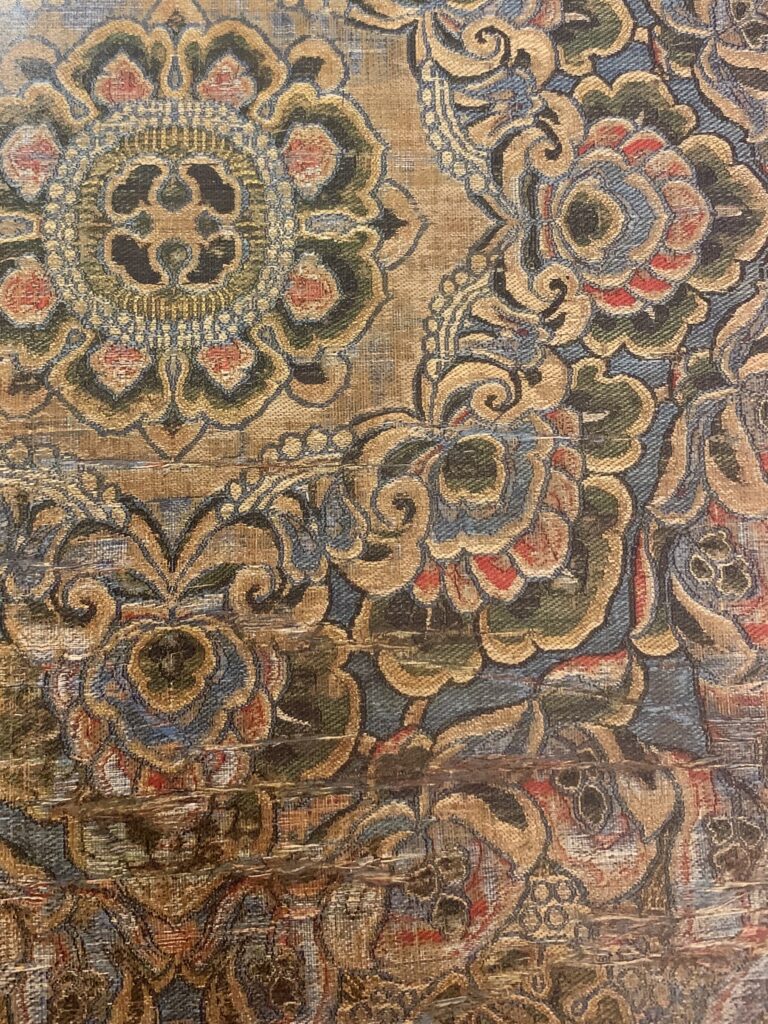

On the last day of our trip we returned to the place where we started—to the Tokyo National Museum. We came to see the second rotation of the Shōsōin exhibition and were highly rewarded for coming back. It was the renewed textile section that caught most of our attention. Fragments of a patterned Tang dynasty nuki-nishiki silk (weft-faced compound twill), once sewn together into a bag for a biwa lute, stroke us with their vivid colours and the high quality of the weave. The central decorative element karahana, or the Tang rosette, was rendered in nine colours on a clear blue ground. Each flower petal was composed out of five different shades, which not only added depth and volume to the lotus flowers but almost followed the aesthetic principles of buddhist painting.

Replica of the biwa lute bag, Shōsōin

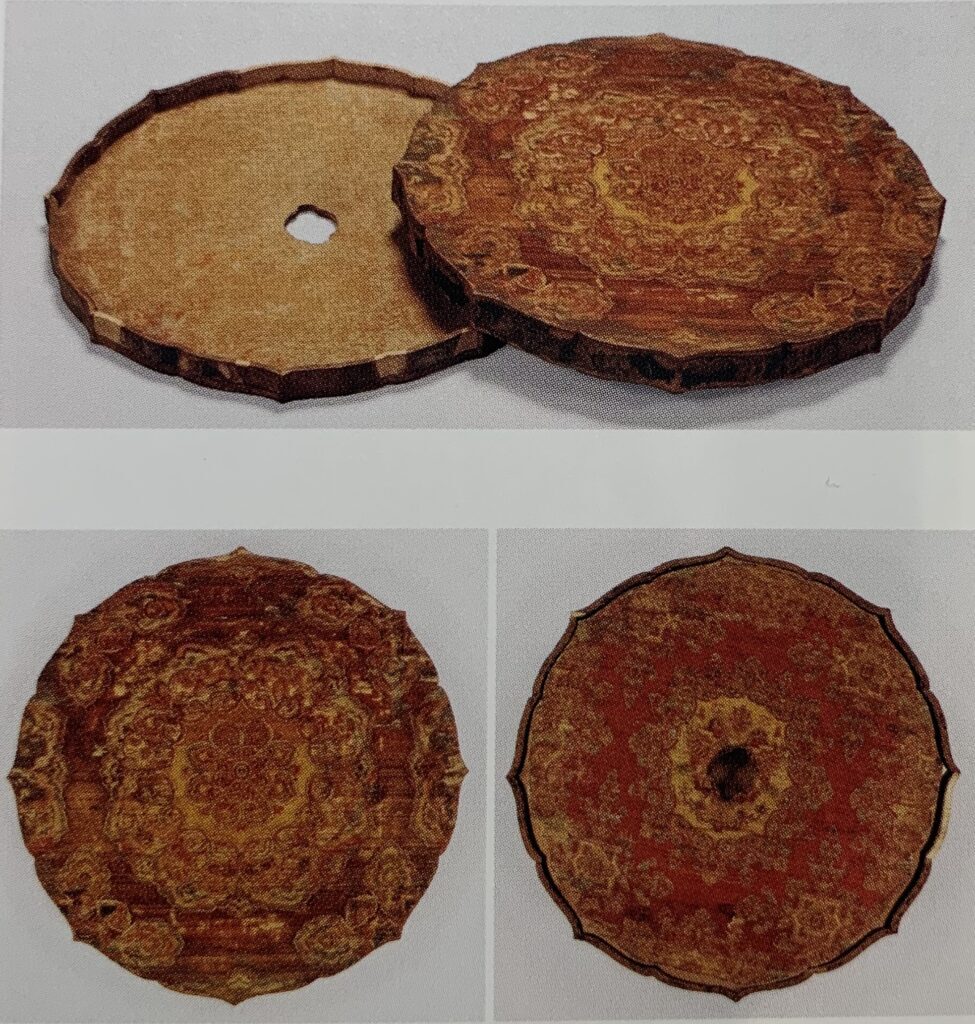

As we encountered the karahana painted on multilayered gowns underneath the “foreign” armours of the dynamic wooden sculptures of the heavenly guardian deities and on the dry lacquer sculptures of Buddha’s disciples at Kōfukuji, we started to think about material translations in different media. One fascinating object we saw at the Shōsōin exhibition in Nara—the eight-lobed wooden Tang mirror case covered with a karahana-patterned silk—may provoke further thoughts about the relations between actual silk covering a wooden core and its painted replications.

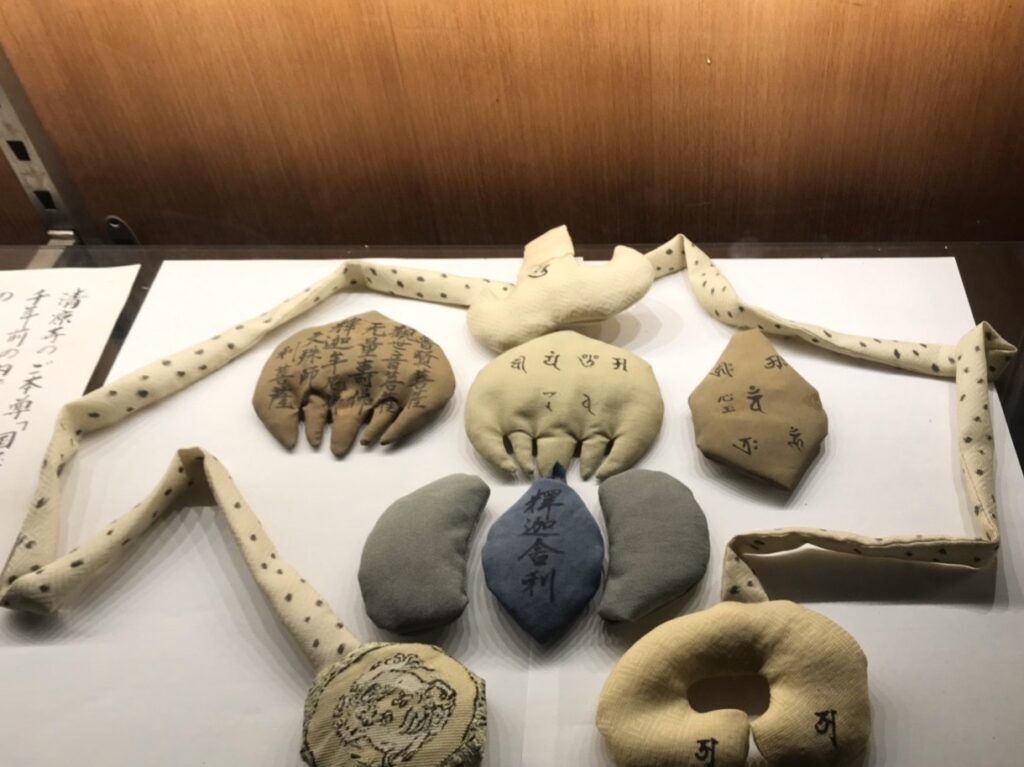

We have seen a number of different material surfaces evoking textile patterns throughout the trip. Painted wood, dry lacquer, but also paper, like the scroll displayed at the Thirty-Six Immortal Poets exhibition in Kyoto, emulating a metallic embroidery or a brocade with its floral decoration applied with mica powder. On the other hand, certain textiles seemed to refer to other materials, for example by resembling hanging metal temple banners through radiant embroidery, or by “becoming” anatomic organs and corporal fluids inside the “true icon” of the Shakyamuni Buddha sculpture at Seiryōji.

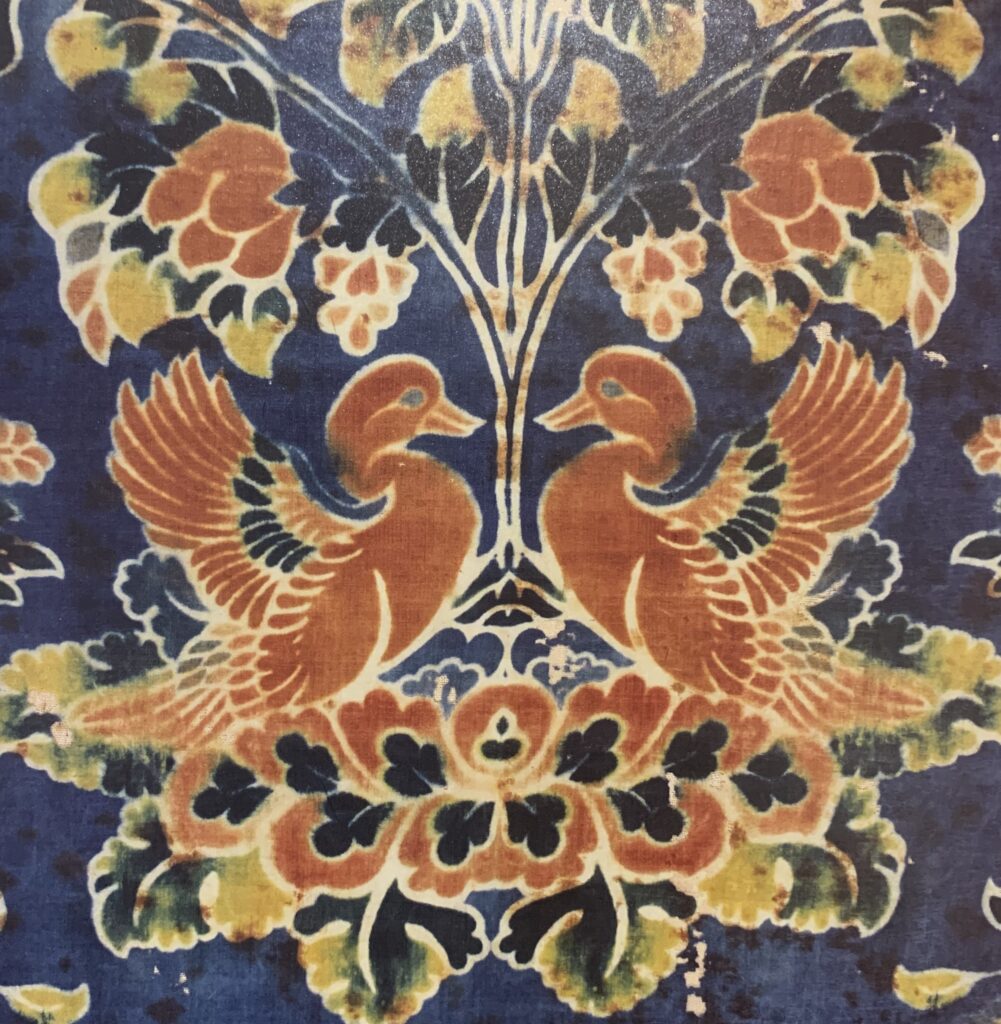

Next to the lute cover fragments we saw the karahana motif on a bigger scale, assembled out of multicoloured felt pieces on the kasen rug with a similar deep blue ground. An other blue-grounded textile object was the joku mat for a buddhist offering table with paired ducks on a lotus flower applied with the kyokechi resist dyeing technique. In the vitrine of preserved scraps we even saw tiny fragments of chain stitch embroidery on blue ground. The technical variety presented in the exhibition reminded us to treat the generalizing term for the medium of “textiles” with more caution.