During my time as part of the Global Horizons project, I examined aspects of Iberian imperialism in Asia and artistic production in the larger Indo-Pacific region through the lens of export lacquerware in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Its focus is a type of lacquerware made in Japan as well as Southern China for a European market. These pieces are known in modern scholarship as “Nanban” lacquerware, meaning “Southern Barbarian” in Japanese. Local artisans responded to the influx of Iberian merchants and missionaries by modifying their craft. After extracting and refining the sap of a species of trees common to East Asia to yield the lacquer polymer, they applied various decorative techniques of embedding gold powder and bits of mother-of-pearl upon successive layers of the wet, binding substrate. This research examines lacquerware’s production and afterlife from the perspective of maritime trade, looking at its production and movement through the port cities of Goa, Macao, Nagasaki, Manila and Acapulco. A process of material layering inherent to the lacquer tradition— that is, of piecing together and binding different elements upon a single surface— parallels these objects’ alterations and material accretions in the hands of multiple far-flung recipients.

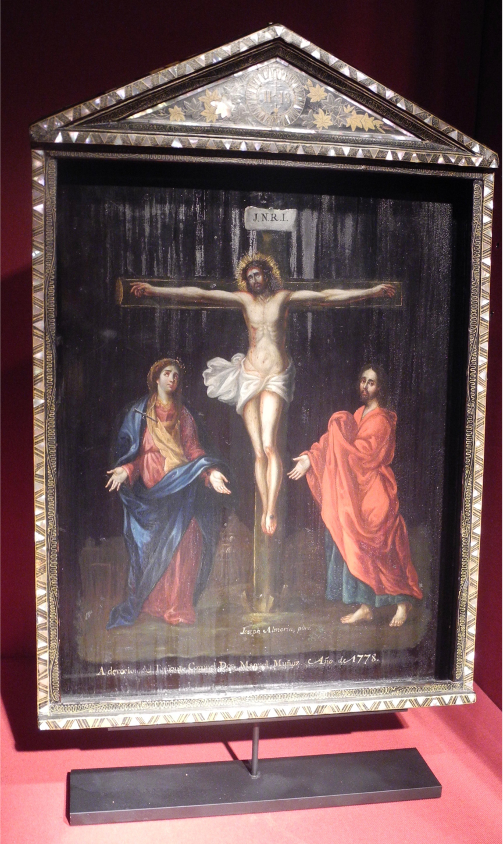

Fig. 1: Portable lacquered shrine (1580-1630) with crucifixion painting (signed by Joseph Almorín, 1778), collection Jorge Welsh, Lisbon.

The portable shrine (fig. 1) shown here exemplifies the continuous “layered” artistic histories created through this maritime zone. Produced in Japan for a Catholic consumer base at the turn of the seventeenth century, it traveled across the Pacific to Colonial Mexico, via Manila. It landed in the hands of a local artist who painted this picture of the Crucifixion directly upon its lacquered ground, creating a shimmering surface of glistening paint, gold and pearl. This shrine testifies to the disparate materials and distant makers who were spread across wide geographical, temporal, and cultural coastal realms.

My time at Global Horizons offered the opportunity not only to conduct research and visit local collections, but also a crucial place to workshop ideas for an essay and wider book project with the scholarly team. The generous comments, discussions, and suggestions shared among the group offered me a space to reconsider the temporal ramifications of “layering” as an art historical methodology, one that subsequently moves beyond the frameworks of hybridity that have long pervaded discourses of cross-cultural contact. This meant not only addressing the multiplicity of materials and makers which compose these travelling objects, but accounting for the aesthetic effect that such layering creates.

These reflections coincided with visiting collections to examine comparative objects traded along Indo-Pacific routes and their subsequent surface effects. This included a visit to the Vitromusée in Romont, which is dedicated to the arts of glass. The collection holds one of the largest collections of reverse-glass painting in the world. This process entails painting an image on a piece of glass and viewing the finished picture through its overturned side. While the technique has precedents in antiquity and the medieval period, it found a new stage of development in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in Northern and Southern Europe, particularly in the production of popular devotional images (fig. 2). The sheet of glass acted as a protective layer for the image, making it an equally portable medium which accompanied missionaries on their travels to Asia. This would initiate fabrication of reverse- glass painting in India, Japan and China, even prompting an export production in the Portuguese colonial enclave of Macao (fig. 3).

The Indo-Pacific operated as a space for the encounter of different light reflective technologies, including reverse-glass painting, copper painting, mother-of-pearl, featherworks, and lacquerware. The case of reverse painting on glass becomes particularly interesting in relation to lacquerware, as many European observers compared lacquer’s translucent qualities of glass and mirrors. In both the lacquered export shrine and reverse glass paintings, the experience of viewing the devotional picture is articulated through a translucent and light-reflective exterior. However, while scholarly discussions of surfaces often focus on an object’s optical effects, this made me consider the tactility of these materials. Indeed, lacquer and glass painting possess a smooth and seamless surface, which invites touch. Furthermore, in a pre-industrial era, smooth and seamless surfaces entail a labor-intensive production process, one that paradoxically conceals any hint of manufacture. As a metaphor and model for this project, “layering” highlights an accretive multiplicity of makers and materials as the world became connected through new systems of exchange. At the sametime, it can also inform acts of artistic superimposition and colonial erasure in an era of imperialism. (Sam Luterbacher)