Our only day in verdant Nara, the first extant capital of Japan, offered a compelling overview of sites and sculpture from the eighth century to the twelfth, and beyond. We began at the Fujiwara family shrine of Kasuga, walking through the deer-inhabited parks to arrive at the site on the outskirts of the ancient city, just before the primeval forest into which no one can now enter. Vermillion stained gates marked the end of our ascent, where we heard morning chants. The Shinto shrine was an apt place to start, as it is a site where the dieties are manifested in objects other than iconic sculpture – one such site was a massive, gnarled tree, marked as sacred with a rope belt and paper ornaments.

Beginning with these aniconic embodiments of the Kami deities laid the foundation for thinking about the forms and media used for the iconic figures created for the Buddhist pantheon. Our day in Nara was exceptionally full because of the special openings of temple sculpture collections to celebrate the imperial coronation in the last weeks, so we were able to see, to ponder, and to discuss a large number of the true masterpieces of early Japanese sculpture.

The 16 meter tall bronze Buddha of Toda-ji, glimmering in the bright sun, was an exception, not the rule. As impressive as he was, bursting out of his special Great Buddha Hall built around him, it was the life-size scuptures in wood, clay and lacquer that kept us transfixed throughout the day, at Todai-ji (including the rarely-opened Hokkedo), Kofuku-ji, and the Kofuku-ji treasure hall.

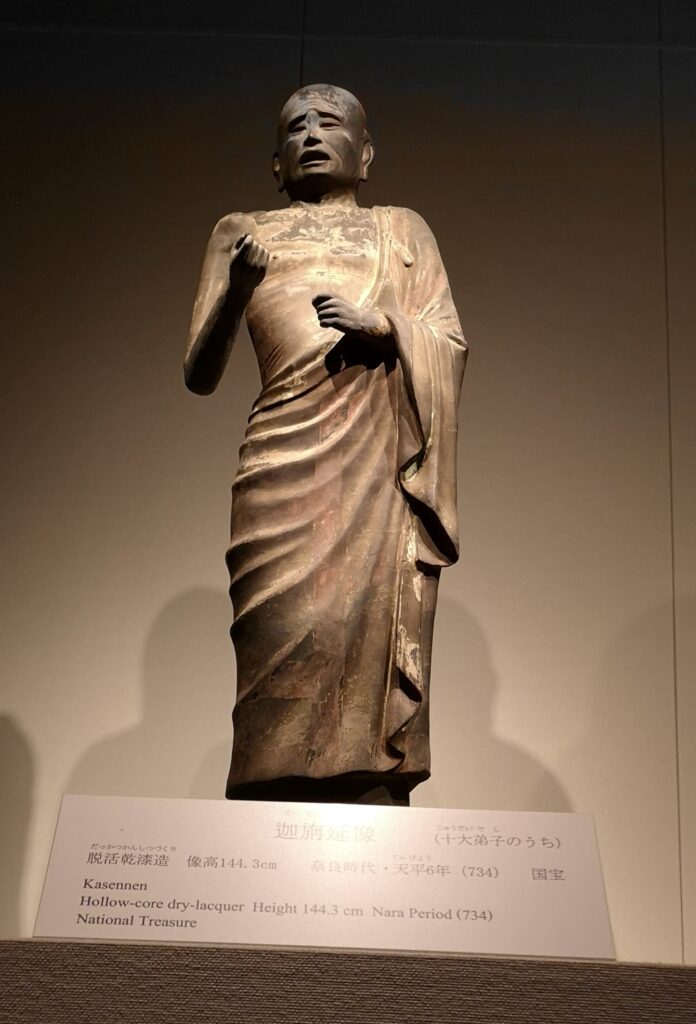

The dry lacquer sculptures at the treasure hall, essentially thin bodies of lacquered textiles with a wood and wire armature, were light, delicate, and waif-like – and it was hard to say where this was due to medium, due to the iconography of the asectic disciples, or to their slim profile to fit the whole group upon platform. I have to say, that these lacquers contrast strongly with the more-corpulent gilt lacquer of Kuse Kannon, though on a solid wooden core, that I had seen earlier at Hōryū-ji (with his chubby cheeks and fleshy red lips). But it is the expressions of the learned elderly men depicted in these figures that holds attention, their furrowed brows, down-turned eyes, and sometimes slightly smiling lips, like they are hiding a delicious secret. Kris remarked that the hollowness of the dry lacquers, paired with these carefully rendered (if not also closely observed) facial expressions, leads to an impression of deep interiority here. The figures seem to enjoy a veritable interior life.

While it might seem improbable to skip over the contemporary Nara-period clay Four Divine Kings of the Todai-ji Hokkedo, the verisimilitude of their foreign armour and the ferocious expressions appropriately protecting the Buddha, it was the question of interiority that kept resurfacing in our discussions. This was brought to the fore when we were joined by Mary Lewine, who is currently working at the Nara National Museum, but whose dissertation is on a late Heian “stuffed“ sculpture. The question of why materials were included in the cavities of wooden sculptures of the later Heian and Kamakura periods, and what role they played was brought up again and again. Kris noted that it was the shift in sculptural process to wooden (polychromed) sculpture, and the need to hollow out the wood to prevent cracking, and the development of a piecemeal, assembled figural sculpture that left spaces in the figures for such insertions. The insertion of devotional materials, sutras, or relics compared to the contemporary practice of inserting extremely mimetic rock-crystal eyeballs into the sculpture. In the morning, Kris aptly critiqued the notion (deeply occidentalizing) of animation. Rather, as Mary explained, these extra-sculptural materials are better conceived as offerings to the deity, or petitions, materials that further knit the deity figured to the patron or community that commissioned, and/or worshipped it.

However, the seated Six Patriarchs of the Hossō school, at Kōfuku-ji from the late Heian period, by the sculptor Kōkei, sitting quietly in the dusk-like light of the hall, their eyes glinting within their wizended faces, the flash of a glance, for me were profoundly present.